PART SIX: THE END

The Hanging

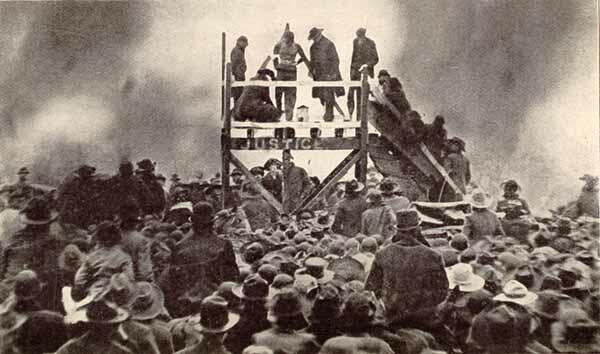

At the time convicted murderers, Jean Baptiste and William Chevis, had received their original reprieve in the summer of 1896, it had been almost a year since Dr. Duchesne T. Courtney’s killing. After T.S. Fontenot’s term had ended on June 22, 1896, H.H. Deshotels became the new sheriff and assumed the responsibility of arranging the brothers’ executions.1 With the November 06, 1896 execution date fast approaching, Governor Foster granted Jean Baptiste another reprieve because he had become sick.2 Thus, only William would face the noose on the appointed date; the hanging would take place within the confines of the parish prison courtyard at 1:00 that Friday afternoon. A mixture of lingering symptoms of the same illness Jean Baptiste had contracted, the weight of his costly sin, and impending sense of doom caused William to collapse upon rising that morning. Apparently, “he would not speak to anyone except his spiritual adviser, [and] he had to be dressed by deputy sheriffs, not having the strength enough to even dress himself.” Meanwhile, witnesses – some mournful, some as eager as bloodthirsty vultures – started filing into the yard at 12:15 p.m.3

Rev. Father John Engberink only had begun pastoring St. Landry Catholic Church in the spring of 1896, and ministering to the Chevis brothers was one of his first and most impactful acts of service to his black parishioners.4 William must have been in good standing with the Church, as Engerbrink administered the Last Sacraments (most likely those of Reconciliation and the Anointing of the Sick) at 12:30 p.m. The Clarion presented the order of events that followed5:

- “At 12:35 Mr. C.F. Garland, Chevis’ attorney, asked the sheriff that the execution be delayed as long as possible in order that he may make a last effort to save his client.” Sheriff Deshotels acquiesced and adjourned the crowd until 2:30 p.m.

- Beginning at 2:00 p.m., “the witnesses filed into the jail yard again, and the last effort of Mr. Garland having proved futile, everything was made ready for the execution.”

- At 2:24 p.m., Rev. Father Engberink led the procession up the stairs to the scaffold, followed by the sheriff and his assistants. William “was so weak from fright that he had to be almost carried…” The assistants could feel that “his legs up to the knee were as cold as ice” and watched as “cold perspiration rolled from his face and body.” To all those watching, William was a “pitiable sight”.

- At 2:30 p.m., having read the death warrant with his “firm, steady voice…the sheriff cut the rope, and Wm. Chevis dropped down into empty space.”

- By 2:48 p.m., William’s twitching and struggling finally stopped. Coroner Daily and medical doctors, B.A. Littell and L. Daly, pronounced him dead.

- Immediately, William “was cut down, placed into a coffin, and…interred in the [St. Landry] Catholic cemetery at this place.”

Consumption

Meanwhile, Jean Baptiste languished in his jail cell, crying himself to sleep at night when he thought of better times in his life or when he imagined how William had suffered on the same scaffold on which he would hang soon. Also, he just couldn’t overcome this illness that had been plaguing him for the last few months. At first, he kept getting feverish, and he felt tired all the time. There was a cough going around the jail cell, but he thought he would get over it, just like William apparently did. He didn’t. Now, he was coughing up blood, and a fire burned in his chest. Sometimes he felt really cold, and, at other times, he couldn’t stop sweating.6 The jail had been “severely condemned by several grand juries as unworthy to be left standing in a Christian community…it [was] so open to the storms of winter that several deaths [had] occurred among the prisoners…because of the neglect of a majority of several police juries to give that relief that humanity demands…”7 It was no surprise, then, that Jean Baptiste died on Thursday, January 14, 1897, of consumption (i.e., tuberculosis), before he could be executed.8 Jack Melancon, an Opelousas resident, buried Jean Baptiste’s body as the final act in a two year-long tragedy.9

Final Thoughts

This blog series emanated from my desire to answer the research question, “Which of Leontine Chevis Taylor’s brothers were rumored to have been hanged and incarcerated for murder?” As their great-great niece, it has been a deeply sorrowful task to sort through some of the details of their brief lives and their disreputable deaths. I finally identified their names by assembling clues from the account shared by my Aunt Olivia, searching available court and church records, and scouring local newspapers of their day. Jean Baptiste and William Chevis are the brothers who were buried over 125 years ago after being convicted of the shocking and fateful murder of Dr. Duchesne T. Courtney. I clarified Aunt Olivia’s report of the circumstances pertaining to the incident, namely that members of the Chevis family were arguing loudly during a gathering on their own property when they were interrupted by Dr. Courtney and his friends; that my third great grandmother Leontine Chevis, indeed, did feel threatened by Dr. Courtney; and that her sons responded violently to his intrusions, with at least one of them contributing to his death. I also learned that, although both brothers were sentenced to hang for murdering Dr. Duchesne T. Courtney, Jean Baptiste ended up dying in jail before he could reach the scaffold.

Bias in the Media

There were several aspects of my findings that stood out to me. Most salient are the elements in the case that could have prevented the Chevis brothers’ murder conviction and consequent deaths: apparent bias in the media; reasonable doubt; and motive. First, in terms of bias, editors included unverified and unofficial data that colored the public’s understanding, opinions, and judgments about the crime before they had obtained the details of the incident from the eyewitnesses or from the coroner’s inquest jury. The very first report, for example, stated that there were three Chevis men involved in Dr. Courtney’s death rather than the two who were ultimately convicted. It is not even clear, at first, which of the Chevis families in the area were being referenced; getting this information wrong could have resulted in misplaced vengeance. Secondly, I was surprised at how quickly newspapers reported Dr. Courtney’s death as a premeditated and wanton murder rather than an act of self-defense or a crime of passion. For instance, in its story headlined, “Dr. D.T. Courtney the Victim of a Conspiracy – Enticed to a House by Cries,” the New Orleans’ Times-Democrat reported, “It is beyond doubt that this was a concocted plan and the cries were made to get Dr. Courtney there to murder him.”10

Finally, editors (particulary those of the St. Landry Clarion) included derogatory terms such as “nigger”, “old hag”, and “scamp” to describe members of the Chevis family. In one article, the Clarion associated words like “honest and intelligent”, “unimpeachable”, and “superior” with Whites while describing Blacks with words like “depraved”, “fiendish”, and “bloodthirsty”. The bigoted values paraded by the newspaper editors may have been related to their sense of grievance and sentimentality about the end of the institution of slavery:

“This [depraved] condition exist [sic] almost exclusively with the younger generation, born since the war, who have been made to believe the Northern radical sheets and local vote brokers that they should be on an equal footing with the whites, and are being deprived of their just rights. How many crimes can you trace to the door of the faithful old darkey that was reared by ‘massa’ on the plantation?”11

Reasonable Doubt?

I’m no lawyer, but, in terms of the case itself, it seems that the inconsistencies in witness testimonies would have made it difficult to identify which Chevis brother had dealt the death-inducing blow to Dr. Courtney. One witness saw William inflict the first blow, while Leontine Chevis alleged that Alexandre Guilbeau struck Dr. Courtney. Guilbeau stated that Jean Baptiste had struck Dr. Courtney the second time, while Louis Jackson said that William administered both blows and that Jean Baptiste had not touched him at all. The possibilities are that William alone was guilty of killing Dr. Courtney; William’s first strike injured him, but Jean Baptiste’s second blow finished him off; or that Alexandre Guilbeau, and not either of the Chevis brothers, struck and killed Dr. Courtney. Because no one with the appropriate authority was invested enough to investigate these matters further, significant questions remain unaddressed in the public record, including the possibility that Mr. Guilbeau was culpable in some way.

What Was Their Motive, and Did It Matter?

In terms of intent, it doesn’t seem that self-defense and/or defense of their mother were allowable motives for killing Dr. Courtney. Further, there was no allowance given for the possibility that the brothers rashly overreacted in drunken or impassioned indignation. William was only sixteen years old when Dr. Courtney was killed, and he was seventeen when he was hanged. Yet, there was no leniency granted for William’s minor status and immaturity, which, today, are seen as impediments to being able to consider the long-term consequences of unchecked emotional responses. As a side note, even Jean Baptiste was relatively young, dying at 30 years old with no wife or children.12 It seemed that the public’s and the court’s only explanation for Dr. Courtney’s death was murder for murder’s sake. As for the suggestion that the Chevis’ conspired and enticed Dr. Courtney to their yard, what would have the reason for such a plan? Had the Chevis family and Dr. Courtney previously had a dispute of some sort, or was it simply “the fiendish and blood-thirsty hatred for the white man” harbored by the capricious “young buck” Chevis boys that led them to random violence?13

Lessons Learned

Justice, an anonymous writer to the Opelousas Courier, explained the situation aptly,

“Considering the case in its entirety, and conceding, for the purpose of argument that both the accused had participated in bringing about the death of the Dr., according to the evidence given on the trial of the case and the circumstances surrounding the killing it would be judicial murder to hang these accused. They did not commit murder. The most ultra view that can be taken of it is that they committed manslaughter…To commit murder, the intention to kill must come to and be considered by us in our cool, quiet, sober moments, when we are not moved and animated by any feelings of resentment, excitement or anger…the accused were at their home, their father’s cabin…they had been drinking, and were quarreling and fighting among themselves…at this hour, and while they were in a state of excitement and anger caused by the quarrel among themselves, the Dr. appears on the scene and in less than a minute receives the two blows from which death resulted…All of the facts surrounding the killing of Dr. C. show most conclusively that it was unpremeditated. The blow was inflicted with an instrument – a stick – to which no evil intent could be attached, and which was on the ground in the yard, where it had been for months before; all of which shows that no preparation whatever had been made for the killing.”14

It was shameful enough that young Dr. Courtney’s life was cut short so tragically. Perhaps if Justice’s plea had been considered carefully, Jean Baptiste and/or his brother William might have been sentenced to the state penitentiary instead of death. Perhaps at least one of the men would have had the opportunity to establish meaningful relationships and left a more inspiring legacy in our family’s collective memory. As it is, both Dr. Courtney and the Chevis Boys are gone, and we are left with enduring lessons:

- We must control our emotions, or we will have no control over our lives. As the Biblical proverb says, “If you cannot control your anger, you are as helpless as a city without walls, open to attack.”15

- “Capital punishment is a necessity, but when an execution is tainted with suspicions of persecution…it will do incalculable harm;”16

- “No man should deny to another his legal rights – be he rich, be he poor, be he as white as snow or as black as ebony. The smallest midget in our parish, when before the courts, should feel that he stands on a level with the tallest giant; the poorest man should feel as strong and powerful as his richest neighbor. Courts of justice, like death, should make no distinction between individuals.”17

Thank you for reading this series about the Jean Baptiste and William Chevis’ convictions for the murder of Dr. Duchesne T. Courtney of Coulee Croche, St. Landry Parish, Louisiana. My goal was to demonstrate the use of newspaper research in solving genealogical puzzles and how to present your findings in a narrative format. Let me know how effectively I met my goal and how you plan to use newspaper research in your family history work. Constructive feedback is appreciated!

FOOTNOTES

- “To Hang: The Chevis Brothers Will Expiate Their Crime on November 6,” St. Landry Clarion (Opelousas, Louisiana), 24 October 1896, p. 3, col. 3; digital image (https://www.newspapers.com/image/174396583). Also, Bobby J. Guidroz, “Did You Know? St. Landry Has Had over 30 Sheriffs in Its Existence,” Daily World (https://www.dailyworld.com/story/opinion/columnists/2016/05/22/did-you-know-st-landry-has-had-over-30-sheriffs-its-existence/84662126/), 22 May 2016 .

- Willie Chevis, Abbeville Meridional (Abbeville, Louisiana), 14 November 1896, p. 2, col. 1; digital image (https://www.newspapers.com/image/64170348).

- “Died on the Scaffold,” St. Landry Clarion (Opelousas, Louisiana), 07 November 1896, p. 3, col. 2; digital image (https://www.newspapers.com/image/174396975).

- Carola Lillie Hartley, “Life Long Dedication of Father John Engberink,” Daily World (https://www.dailyworld.com/story/news/2018/11/15/lifelong-dedication-father-john-engberink/2015379002/) 15 November 2018.

- “Died on the Scaffold,” St. Landry Clarion (Opelousas, Louisiana), 07 November 1896, p. 3, col. 2; digital image (https://www.newspapers.com/image/174396975).

- Dean Shaban, “Tuberculosis (TB): Causes, Symptoms, Treatment,” WebMD (https://www.webmd.com/lung/understanding-tuberculosis-basics), 27 July 2023 .

- Letter to the Police Jury, Opelousas Courier, 22 February 1902, p. 1, col. 6; digital image (https://www.newspapers.com/image/168311963).

- Jean Baptiste Chevis, Abbeville Meridional (Abbeville, Louisiana), 23 January 1897, p. 2, col. 1; digital image (https://www.newspapers.com/image/68057739).

- Police Jury Proceedings, St. Landry Clarion (Opelousas, Louisiana), 06 March 1897, p. 2, col. 4; digital image (https://www.newspapers.com/image/174309367).

- “Murdered by Negroes,” The Semi-Weekly Times-Democrat (New Orleans,, Louisiana), 24 September 1895, p. 4, col. 4; digital image (https://www.newspapers.com/image/148754068).

- “Will Hang: Willie and Jean Bte., Murderers of Dr. Courtney to Hang for Their Crime,” St. Landry Clarion (Opelousas, Louisiana), 12 October 1895, p. 3, col. 2; digital image (https://www.newspapers.com/image/174614912).

- Death Warrant Read, St. Landry Clarion (Opelousas, Louisiana), 13 June 1896, p. 1, col. 2; digital image (https://www.newspapers.com/image/168317540).

- “Will Hang: Willie and Jean Bte., Murderers of Dr. Courtney to Hang for Their Crime,” St. Landry Clarion (Opelousas, Louisiana), 12 October 1895, p. 3, col. 2; digital image (https://www.newspapers.com/image/174614912).

- “The Chevis Case,” The Opelousas Courier, 09 November 1895, p. 4, col.4; digital image (https://www.newspapers.com/image/168365180).

- Proverbs 25:28 (Good News Translation).

- Governor Foster Fixed the Date of Execution, The Opelousas Courier, 24 October 1896, p. 1, col. 2; digital image (https://www.newspapers.com/image/168324076).

- “The Chevis Case,” The Opelousas Courier, 09 November 1895, p. 4, col.4; digital image (https://www.newspapers.com/image/168365180).