“You live as long as you are remembered.” – Russian Proverb

Usually, summertime is jam-packed with the days of family. Mother’s Day has already passed, but Father’s Day and National Children’s Day are coming. July will spark with fireworks and barbecues for Independence Day and family reunions. In these summer days of 2020, when family is on our minds and unity is more important than ever, remembering the mothers, fathers, and extended family who made us possible is the perfect quarantine activity. In fact, that’s what I did this Mother’s Day. In the midst of reading my cards and hugging my babies, I spent the morning crying as I wrote a poem about my mother who died unexpectedly five years ago. In it, I expressed my gratitude for her and her sisters (my aunts have done a lot to love and support me over the years).

What I didn’t write about that was also coloring the emotion of the poem was the struggle that parenting presents and how each and every day I grapple with how to do my job better than I did yesterday. I wondered how my people lived these same struggles. What dilemmas did they face? What impacted their choices? What messes did they create, and how did they fix them? Given my African-American roots, I inevitably started thinking about the complexity of my family’s experiences.

It seems like the kind of appreciation inspired by the summer holidays could have been difficult to develop for families whose lives were disrupted by the practices characterizing slavery. Male and female slaves were not allowed to marry legally, but they did create formal unions and build relationships. Often, slaves were sold without any regard for maintaining a family’s physical and emotional bonds. These so-called husbands and wives frequently were separated, sometimes forever; fathers, then, might lose the opportunity to welcome an unborn child to the world. In cases where slaves were born of a process of breeding rather than out of the genuine love and desire to have family, an individual might not even know his parents’ names! The result today is that many descendants of enslaved people in the U.S. are unable to trace their family history to before 1870 (that’s when their ancestors names’ were first recorded in federal records). Thanks to the research collaboration with my genealogy colleague and cousin, Barbara Johnnie, I can trace some of my mother’s paternal, African ancestry prior to that time.

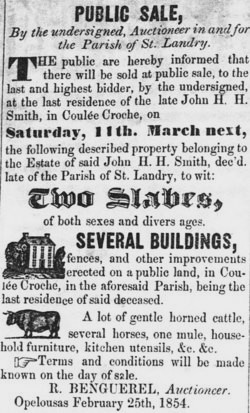

To tell you this family’s story, I’ll start by sharing a little about John H.H. Smith of Halifax, Virginia. While most of his family relocated to and died in Georgia, Smith settled in Louisiana. He married Celeste Savoie on June 16, 1812 in Opelousas, Louisiana, and, in less than a year, the couple invested in a new property. According to a Sale of Slaves recorded on February 15, 1813 in Opelousas, John H. H. Smith bought “a certain negro woman slave named Mary, aged about twenty years together with her child named Maria, an infant mulatto” from Thomas Williams for $510. Given that Celeste gave birth to a child just two weeks after the purchase (i.e., March 03, 1813; the child died the same day), the Smiths probably bought Marie to help Celeste with raising their growing family. John H.H. Smith then enlisted as a member of the 16 Regiment (Thompson’s) of the Louisiana Militia. After completing his military service, Smith returned to St. Landry Parish, Louisiana.

There is no record of any more slave purchases or acquisitions until 1828 when he purchased a 38 year-old “a negro woman [slave] named Jude” from the estate of Celeste’s mother. Yet, an 1818 property tax document shows that, in addition to 230 acres of land and over 42 animals, Smith had four slaves. In the 1820 Census, he had that same number of slaves, and we have more information about them: there were two females and one male under 14 years old and one female between 26 and 45 years old. In 1830, there was one male aged 10-24 years old, two females 10-24 years old, and two females 24-36 years old. In a document described later in this post, we find that these additional slaves (i.e., besides Marie, Maria, and Jude) were probably James and Adelaide. An 1825 baptismal record for documents an eight-year-old James who was the son of Marie and slave of John H.H. Smith. There is no such record for Adelaide, but she was undoubtedly the other young female slave. The only explanation for this increase in the number of Smith’s slaves is that Marie had begun a family of her own. By 1840, we see that one of the younger females referenced had started having children as well – Maria.

In fact, by 1846, Maria had borne at least 8 children. A document dated October 03, 1846 reveals that John H.H. Smith and his wife mortgaged “a tract of land being one hundred ninety-eight arpents and the following slaves: a negro named Maria aged about 35 with her eight children to-wit, Edmond, 15; Alfred, 13; Virginie, 12; Doralise, 10; Coralie, 7; Frank, 5; Caroline, 3; and Harrison, 14 months.” Not only does said Maria’s age correspond with that of the Maria purchased in 1813, but the baptism records of several of the children mentioned in the mortgage cite their mother as “Marie Doralise, the slave of John H.H. Smith.”

On March 4, 1848, a public auction was made to sell “all the property belonging to the estate in community between John H.H. Smith and his children, the issue of his marriage with said Celeste Savoie, his deceased wife (except the slaves Edmond and Adelaide)” When Celeste’s estate was settled in 1849, Maria’s family was mentioned again. A document dated January 19, 1849 shows that the auction resulted in the sale of the following slaves:

- James [Marie’s son, Maria’s brother], a negro boy about 30 years sold to John W. Smith [Smith’s son] for $1050.

- Alfred [Maria’s son], mulatto boy about 15 years sold to Onezime Guidry for $1,030

- Virginie [Maria’s daughter], mulatto girl about 13 years sold to Alexis O. Guidry for $910

- Doralie [Maria’s daughter], mulatto girl about 11 years sold to Joseph A. Guidry for $300; it was stipulated that she was “not guaranteed,” meaning that she had some sort of defect or weakness of character

- Maria [Marie’s daughter], a mulatto woman about 35 years sold with her 4 children: Coralie, about 8 years; Frank, about 6 years; Caroline, about 4 years; and Harrison, about 2 years, to Leon Thibodeau [Smith’s son-in-law] for $1930.

- Marie [the matriarch of the family], a negro woman about 56 years sold to Robert H. Smith [Smith’s oldest son] for $175

- Judith [probably the “Jude” bought in 1828], a negro woman about 55 years sold to Eucher[sic] Lavergne for the sum of $50.

At this point, we see that Marie watched her family get dismantled before her very eyes. Her daughter Maria’s oldest three children were each sold to three members of the local community’s Guidry family. Maria was able to keep her 4 younger children in her custody at Leon Thibodeau’s house, but her oldest son, Edmond was retained by John H.H. Smith probably because his tendency toward fits reduced his resale value. Marie, herself, appears to have been sold away from not only Maria and her family, but also from her 2 (probable) other children, Adelaide and James. Adelaide stayed in the possession of John H.H. Smith until his death in 1854. At 40 years old, she was purchased by Joseph Smith for $780. As noted above, James was sold to another of Smith’s sons.

Most of the time, when enslaved people were separated from their families, they rarely saw each other again. Fortunately for Marie’s family, her children and grandchildren were purchased by familiar people – John H.H. Smith’s children and nearby neighbors from the same Louisiana community. Moreover, they obviously tried to stay in close contact and in remembrance of their history. One proof of this is that they memorialized each other in naming their children. Harrison, Doralise, Coralie, and Virginie are common names among the Barker descendants. There is not much information available about what happened to Marie, Adelaide, and Frank, but the rest left traces of their lives post-slavery in the historical record.

Maria appears to have had two more children after being sold to Leon Thibodeau: Julia, b. 1848 and Mary, b. 1854. Maria went on to legalize her marriage to the man often cited as her children’s father. One Marie Doralise Casey1 and Harrison Barker secured a marriage contract on October 30, 1869 and were married in the Catholic Church by Rev. Jacob G. Warner on March 02, 1870. John Ashley, F.G Robertson, and Frank Ricks were witnesses of the event. Harrison and Mariah were able to live together as free people for over a decade. They can be found in the 1880 Census living in the second ward of St. Landry Parish only three houses down from Maria’s former slave owners, Leon and Celeste Thibodeau. Several houses away lived their daughter Caroline and her family. A bit farther away but in the same ward, Virginie resided with her daughter Cora Evans and family, and Doralise lived with her husband Francis Glaude and family. By 1900, Harrison had died, and Maria was living with her daughter Doralise and her family2. Death records for Harrison and Mariah have not been found yet.

Edmond was sold to William Smith for $355 when John H.H. Smith died in 1854. Alfred died in 1852 shortly after he was sold to Onezime Guidry. Harrison began referring to himself by John and started a family with his wife. All of Maria’s daughters had children while they were enslaved without the benefit of slave or legal marriage, apparently. Many of the fathers of their children were white men in the local community. Virginie even had several children for her slaveowner, Alexis O. Guidry. There are legal records that show that Doralie, Coralie, and Julia married and built sizeable families after slavery ended. Doralise married Barney Moore in 1862 and appears to have had a relationship with one Francis “Frank” Glaude. Coralie married Don Louis Marks in 1886, and Julia married Frank Malbrough in 1869.

The goal of this article was to share the origins of my Barker family and encourage you to explore your own origins. Until family genealogists began discovering our ancestors in public and private records, we knew nothing about Marie and the foundation she set for the Barker family. Maria (Marie’s daughter) and her children had worked hard to preserve the bonds and keep the knowledge of family history within grasp, but the intimacy of their connections faded away after the first two or three generations post-slavery. People grew apart as the family grew larger over the course of 150 years, but, thankfully, that trend is starting to reverse as we remember our ancestors and reach out to those still living. I can’t explain it very well, but even knowing their names means something to me. I feel more anchored to them, more rooted in history. Knowing this precious little about some of my ancestors’ experiences helps me to emphathize with them…and to feel that they would be able to emphathize with me. BUT, this is not just about me and my family. You, too, can make connections between your past and present and with your living relatives. Remember them, and you may learn more than you expect.

1Interestingly, Maria’s surname on her children’s death certificates was listed variously as Casey and, alternately, Gascey and Jaskle; perhaps this was her father’s surname.

2In 1900, Maria is recorded to have been born in Louisiana; reportedly, her father was born in Georgia and mother in Tennessee. She reported that she had borne 8 of 12 children. In 1880, however, her parents’ birthplaces were listed as Virginia.

Hi Tameka, my name is Dena Hughes and I am a descendant of Virginia Barker. My family home is in Beaumont Texas. Virginia is our family matriarch and we have her lineage from Dr Guidry to the present. Thank you for sharing this essay, I am very happy to have found it.

LikeLike

Hi Cousin Dena! Thank you for writing, and I’m glad I was able to brighten your day. Take care! Tameka

LikeLike